The first time I met Jimi, like I mentioned briefly in one of my other writings on this site, was way back in 1992. We met in the best way possible, I think: in a darkened room, while I was still very young—and, more importantly, high as a kite. We sat together, me and a bunch of people I hardly knew, curtains closed, three or four joints being passed around, and we’d watch The Doors, the 1991 Val Kilmer movie. And I was… dumbstruck. Flabbergasted. In awe. In other words, I was in love. How is it possible, I thought, that one single man can live a life of such magnitude? How is it possible that one single man can cram more life in his twenty-seven years than other people do in ten lifetimes? How can one man be that talented? Use that amount of drugs? And be this beautiful? It’s not fair! Sigh…

And now, all those years later, I find myself wondering, out loud, is it really possible that we live in a world so stark and dark that there are young people on this planet, right now, who do NOT know who Jim Morrison is? No, right…? Please tell me that’s not true… I’m not sure if I want to live in a world like that… Luckily, it doesn’t have to be that way! So, gather round, kids, and let Grampa tell you about the good old days… You see, you little rascals, there was once this time period, right smack in the middle of last century, when your parents’ parents were still young (imagine that!) called The Sixties. It was a time of wonder, and of magical things… Massive, massive amounts of drugs, too… Change was in the air! Society had been suffering under the suffocating blanket of 1950s fake, cramped values for far too long, and now, something was about to give. It was like society itself had hit puberty, flipped a birdie to that square and dreary decade behind him, turned around, and went about to par-TAY! Yeah, baby! FUCK the rules, Mom and Dad! Fuck ’em!

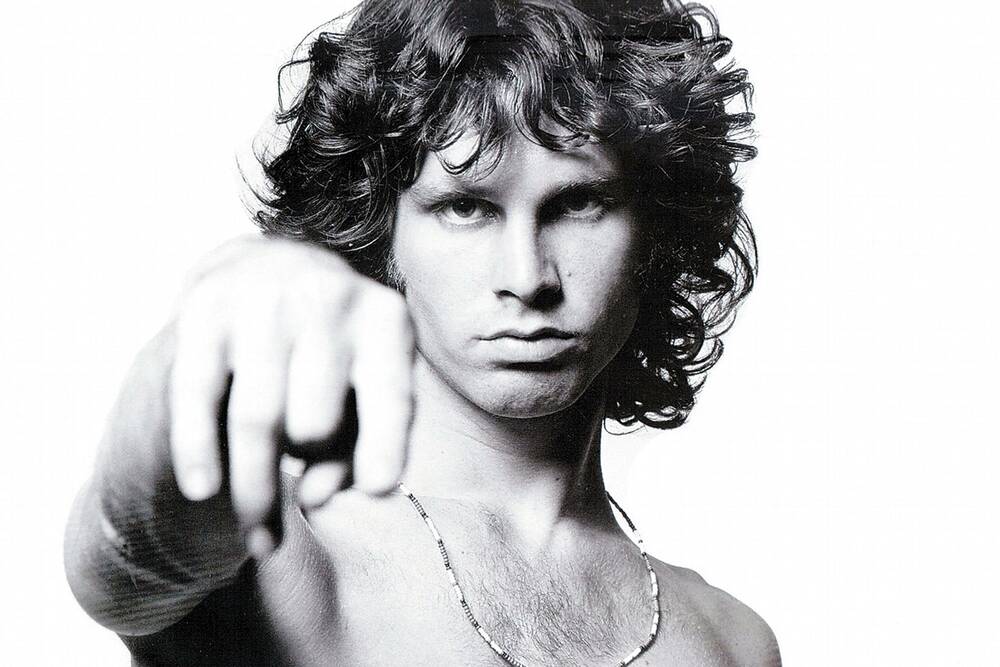

It was in this very spirit of freedom and free sex that there was born a man. He was a musician, poet, Rock God, the object of furious, moist-thigh-inducing admiration from hordes of screaming girls, and boys too, and of angelic, ethereal beauty.

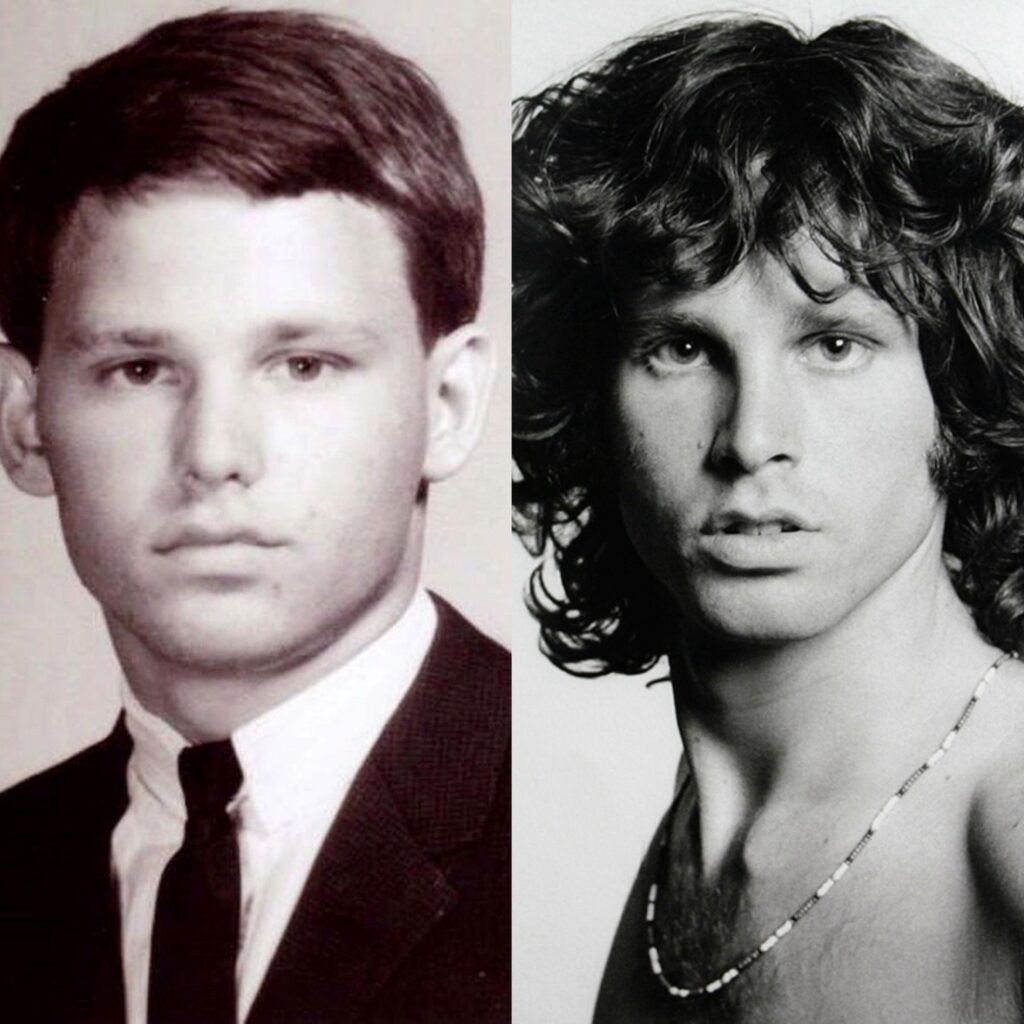

But, before any of that, he was just… little Jimi. Born in Melbourne, Florida, in 1943, the son of a strict Navy admiral and a quiet, dutiful mother who spent most of her life following orders. The family moved constantly, from base to base, and young Jim grew up without roots, learning early how to live inside his own head. He read voraciously—Nietzsche, Kerouac, Blake—and started to think of life as one long, surreal poem. One event from his childhood haunted him forever: a car crash in the desert, where, according to Jim, a Native American lay dying on the side of the road. “That Indian spirit,” he’d say later, “jumped into my soul.” Whether it happened or not doesn’t matter. What matters is that he believed it did. And from then on, he wasn’t just a boy anymore. He was a myth in progress.

Even before music found him, he was already writing like a man possessed. In college, at UCLA, he studied film, but what really consumed him was language — words as spells, rhythm as rebellion. He filled notebooks with dark, electric fragments of poetry about death, freedom, sex, and the end of civilization. He saw himself as part philosopher, part shaman. Nietzsche gave him the idea of the Übermensch — the man beyond morality — and the Beat poets showed him that art didn’t have to behave. By the time he graduated, Jim was living in a small Venice Beach apartment, eating LSD for breakfast and scribbling verses in the margins of his mind. The world to him wasn’t a place to live in — it was something to set on fire.

In the summer of 1965 he ran into Ray Manzarek, an old classmate from UCLA’s film school. Ray asked him what he’d been up to, and Jim said he’d been writing some songs. When Ray asked to hear one, Jim sang a few lines of Moonlight Drive. Manzarek froze. He later said it was like hearing rock music reinvent itself on the spot. Within weeks, they’d found two more kindred spirits: drummer John Densmore and guitarist Robby Krieger. Together they became The Doors — named after Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception. Morrison brought the words, Manzarek the cathedral of sound, Krieger the melody, and Densmore the heartbeat. And just like that, the 1960s had found its dark, beautiful prophet.

The Doors started out playing small clubs on the Sunset Strip. Morrison, at first, could barely face the audience; he’d stand with his back to the crowd, mumbling into the mic, half-singing, half-incanting. But he got over that and soon, he was prowling the stage like a wild animal in heat, a pagan priest in leather pants, summoning storms. By the time they became the house band at the Whisky a Go Go, word had spread. Their sets grew longer, louder, riskier — until one night, after an improvised, drug-fueled performance of The End, Morrison’s Oedipal ad-lib got them fired. It didn’t matter. They’d already been signed.

Their debut album, The Doors (1967), hit like an earthquake. Break On Through, Light My Fire, The Crystal Ship — radio stations didn’t know whether to ban them or worship them. Morrison’s voice became the sound of rebellion itself. Suddenly, the shy poet had become the Lizard King. Money poured in. So did the women, the press, the mythmaking. And Jim, never one to resist a good myth, leaned in hard. He drank more. He tripped more. He provoked, stripped, screamed, and teased his audience like he was conducting some grand social experiment: how far can we go before it all burns down? Each show was theater, ritual, and riot in equal measure. And each one left him a little more lost in the fire he’d built himself.

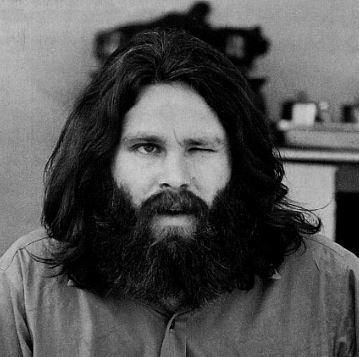

Strange Days, Waiting for the Sun, The Soft Parade, Morrison Hotel — each new album pushed boundaries in its own way, each tour wilder than the last. They became a global phenomenon, their concerts part bacchanal, part spiritual awakening. But with every new city, every flashbulb, every hangover, Jim grew heavier — in body and in spirit. The fame that once thrilled him now felt like a trap. He’d gained weight, let his beard grow wild, and abandoned the leather god image for something closer to a drunken prophet. The others tried to keep the machine running, but Morrison was slipping — from the stage, from the spotlight, from himself. By 1971, weary of the endless cycle of touring, arrests, and scandal, he fled to Paris with Pamela Courson. He called it an escape, a chance to write, to rediscover the poet he once was. But really, it was retreat — the slow fade of a man who had seen too much, done too much, and burned too brightly for too long.

Jim Morrison was more than a frontman — he was a mirror held up to a generation that refused to bow. To the youth of the late ’60s, he wasn’t just a singer; he was liberation incarnate. A symbol of raw instinct and unfiltered rebellion in a world choking on convention. His lyrics broke open the walls between rock and poetry, between art and madness. He made danger beautiful, and beauty dangerous. His shadow never left the stage — it lingers in every artist who dares to speak without permission, in every soul that chooses fire over comfort. Morrison didn’t just define his era; he set it ablaze, and we’re still walking through the smoke.

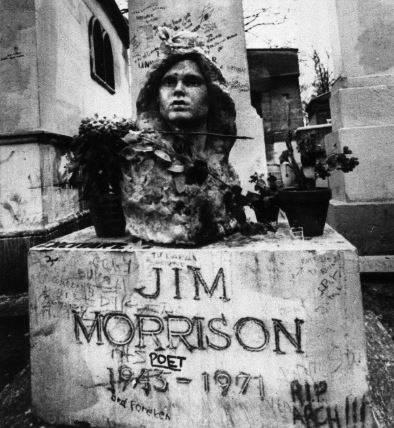

And then, on July 3, 1971, he died. Whether it was suicide or an overdose, we will probably never know. But that doesn’t really matter, does it? Not to me, anyway. His name was Jim Morrison, and I love him. It was this very man, this icon, this whirlwind of chaos and poetry, this dangerously beautiful enigma, this god of leather pants and whispered madness, who went on to not only make some of the very best music ever made, but also to be a god of his time, his generation, and what it all stood for: freedom. True, boundless freedom.

So, there you have it, kids. My Jimi. I, myself, went on to eventually use many, many more drugs than my beloved hero ever did. Also, I’m still alive. So, in a sense, you could say I outdid and outlived one of my own gods. Yeah. I like that. Well, what’s more to say about it? Eight studio albums. One hundred million copies sold worldwide. And counting. An enduring legacy. My eternal love. What more can a man be?

Hey, man, Jimi, man. I miss you, man. I hope you have fun up there. Tell that other Jimi I said hi… I’m sure there are plenty of drugs for the both of you… It’s called Heaven for a reason…

Leave a Reply