After nearly a half-century on the silver screen, Meryl Streep has more than earned her status as a living legend. She’s arguably the greatest actress alive, and certainly up there with the all-time greats. Name it, she’s done it, even if it’s fair to say that she spent more than half her time checking off accent parts like she was channeling the ghost of Paul Muni. And while Sophie’s Choice will always remain her finest hour, I’m more inclined to highlight her smaller, less showy roles as the true measure of her talent. Take films like Adaptation or A Prairie Home Companion: respected, yes, but rarely topping anyone’s list of essential Streep. Instead, critics and audiences alike traffic in the obvious. Big roles, grand gestures, and, if possible, accounts of actual human beings who have lived and died and made their biographies available for Hollywood oversimplification.

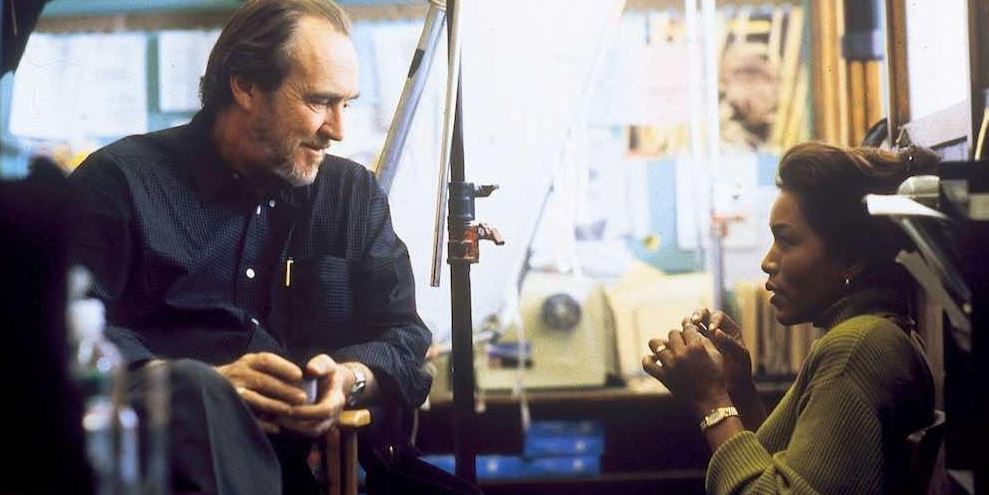

And while nothing will top The Iron Lady for awards bait pandering at its worst, imagine my surprise when I came across 1999’s Music of the Heart. A predictable 223rd nomination for the one actor among us who could generate Oscar buzz for spending two hours in a coma, yes, but also one of the few times I cried out with sheer embarrassment at her obvious slumming. Her dastardly whoring for an easy paycheck. Or agreeing to the equivalent of a Lifetime soaper because she hadn’t anything better to do. Or maybe she knew how bad the entire enterprise was – from leaden direction (by Wes Craven!) to a screenplay so top heavy with cliches it threatened to sink to the Earth’s core – and was determined to prove (to herself most of all) that she could literally do anything short of scatological porn and be recognized by the Hollywood cognoscenti. I’d like to think her eyes rolled most of all at rehearsals.

I usually see every Oscar nominated film and performance, year after painful year, but when one is missed, it’s usually a deliberate omission. While over 25 years have passed since Music of the Heart hit theaters, the premise alone rattles my skull with remembrance as to why it evaded capture. An abrasive white woman (Roberta Guaspari), fresh off a divorce, two kids in tow, decides to move to Harlem to teach a bunch of black and brown kids the violin. That more than covers it, but let’s continue. She’ll be disrespected at first, but after a few classes and immeasurable sass, the teacher wins over the youngsters, also charming a gruff principal in the process. Still more. The kids pull it all together for a concert, where the deafening applause leaves not a dry eye in the house. Even the skeptical parents come around and roar like seals.

With that recital, I thought the movie was at an end, but checking the timer, we still had over an hour to go. What on earth could follow when they most decidedly shot their emotional shot? Pushing the story ten years in the future, that’s what. Because without that, how could we meet the young ladies and gentlemen who had been taught by Roberta over the years and were now, without exception, doctors, lawyers, scientists, and improbably beautiful? All on the fast track to prison or the morgue were it not for some honky with a dream. More than that, though, we needed the obligatory crises of the genre: the funding cuts that threatened to end all music in the known universe, the loss of a prized pupil to a sudden move, the murder of another student, immediately following a fight with the teacher, and, naturally, a new love interest to erase the stench of both the divorce and a first love who refused to commit.

Throughout, Meryl gives it her all – screaming, cajoling, fighting for the power of music – but at no point does she approximate a flesh and blood human being. Every action is at the behest of a screenplay so enslaved to convention, it thinks nothing of throwing in Itzhak Perlman and Isaac Stern in a Carnegie Hall finale. Because the 92nd Street Y flooded. With three weeks left before the big show. And so the legendary musicians, along with several dozen prodigies in waiting, play before a capacity crowd and secure enough funding to keep the school’s music program alive for another three years. And beyond, I’d expect, unless you want Yo-Yo Ma showing up at your next school board meeting. Maybe in the long-delayed sequel.

As Rush once stated, “One likes to believe in the freedom of music.” Given its ties to memories, relationships, nostalgia, and love, who could ever hope to deny its power? And yet, when it comes to the movies, it never quite seems believable as a transformative force. Instead, it’s part and parcel of the national illusion whereby impossible odds are overcome through sheer pluck and perseverance. Where a lone wolf of a teacher, usually underpaid and unsung, so bends the arc of the universe that tragedy yields to triumph with every curtain call. Yes, I know Roberta was a real woman, and no doubt a hundred apple-cheeked youngsters learned Bach one huggable Spring, but I simply cannot accept the fulfillment of dreams in so clockwork a fashion. With no mess, doubt, or nuance to gum up the works. Especially when the Grand Dame of the cinema knew better.

Leave a Reply