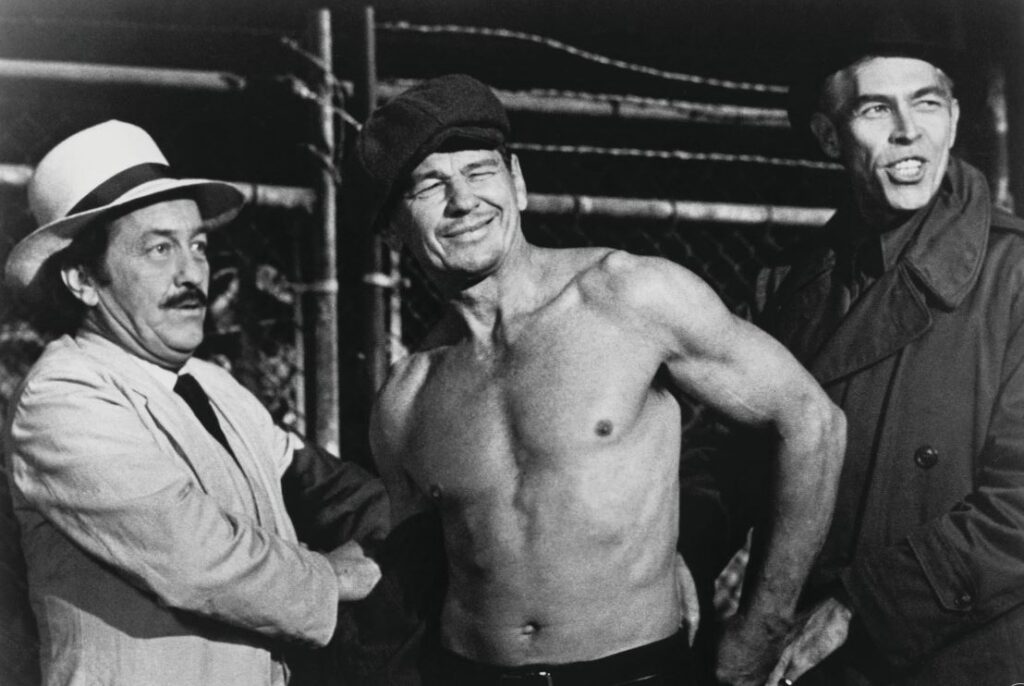

There was a time – we’ll estimate about a half century ago – when a shirtless Charles Bronson was enough. Enough for what depends on the audience, so we’ll rest on the happy medium between anything and everything. But since this was 1975, we’ll narrow it down to a few appropriate cultural touchstones. Enough to erase the stink of Saigon’s fall and an end to the most humiliating war in American history? Yessir. Enough to so outshine Watergate’s betrayal that we’d once again salute and sign on for whatever Washington handed out? Obviously. And with Hard Times, where his fifty-four finely cut years made mockery of the very idea of aging, Bronson both rescued a nation and set a new course for the future. A future with very few words, mind you, but when you’ve redefined chiseled for a generation, complaints will be few and far between.

Because it needs to be said: Bronson’s Chaney speaks less often than just about any central character since The Jazz Singer introduced the human voice to Hollywood. Sure, he negotiates a deal or two and orders some coffee now and again, but in this film’s 97 minutes, minutes that include a half dozen bare-knuckle brawls, several meals, and the seduction of Jill Ireland, we learn almost nothing about the man as we go along. First glimpsed aboard a train to nowhere, by movie’s end he’s disappeared again into the ether, less biographical sketch than a hastily scribbled note. That he takes care of himself, even amidst the hunger pangs of the Great Depression, is obvious, and it’s clear that while he’s broke, rootless, and sans direction, he still finds the time to do a few thousand pushups over the course of an afternoon. He’s certainly a Forgotten Man, but he’s not about to pose for Dorothea Lange. Had Playgirl’s centerfold existed, he’d be June through September.

I know what you’re thinking: how can a man of Bronson’s stature, just a year removed from the career-defining Death Wish, be an Unsung? Isn’t he too big, too beautiful, too central to the very film he inhabits? Undoubtedly fair, but when you make your performance in Death Wish II look like a Paddy Chayefsky stand-in, you more than qualify. Anyone with the audacity to play a man without form, content, desire, or even a semblance of an inner life is what the Unsung was made for. If it were an award, it would be a Chaney. His character is but a brief journey from A to B: appear for a fistfight and get paid for said fistfight. Yes, he has a two-bucks-a-week room, adopts a cat seemingly out of nowhere, and pursues a woman with all the loquaciousness of a mime, but forget trying to understand the man. He’s giving you nothing, and the screenplay is giving even less. God bless a cinematic era when folks just shut the hell up and relied on their wits.

What director Walter Hill’s debut lacks in monologues, it more than makes up in atmosphere. We believe body and soul in his vision of 1930’s New Orleans, a city, then and now, where everything is up for sale. Without anything resembling a stable economy (again, then and now), folks aren’t asked whether or not they can afford to live. You’re simply expected to put up your dukes and battle for the precious scraps that constitute a culture. Even better if you can bring along a knife. And guns, well, they pretty much have an answer for every question. Men arrive, knock people down, and move along, often in the same evening. No need to learn anyone’s name, since they’ll either be dead or long gone by sundown. So yes, it makes perfect sense that as society breaks down even further (it’s not as if New Orleans was ever anything but a rigged casino at sea level), every conceivable interaction would be reduced to men, their fists, loads of cash, and a clear winner and loser. The unemployment rate, then, depends entirely on whether or not you can reduce another’s mug to pulp.

Another review might focus its energies on Speed (James Coburn), Chaney’s handler and all-around manager. He sets the terms, places the bets, and divvies up the cash after all the teeth have been swept into the bin. He’s a fascinating figure to be sure, but a little too fleshed out to meet the moment. He’s reckless, careless, and greedy, and his motives reek of the obvious. Not flaws, mind you, just the skin he inhabits. In the end, you just care more about the mystery. And then there’s Poe (Strother Martin), Chaney’s cut man. He too proves quite alluring, with just enough ambiguity to keep us all guessing, but let’s face it: Martin would keep me engaged while taking a nap. How and why he’s here could fill a screenplay all its own, which makes him too typical of an Unsung. You want to know more, so you invest in the process. A backstory, a point of view, perhaps even a philosophy. Not so with Chaney. There’s even less than meets the eye.

Instinctively, I like to champion stone-faced, inarticulate apes, because if I don’t, who will? We’re a civilization obsessed with therapy and getting to the bottom of things and for once, I’d like someone to give that entire notion the finger. Bronson made a fortune doing exactly that, time and time again, but here, he didn’t even pretend to belong to anything: not a couple, not a family, and certainly not a city or state. Still, at the end, he hands Poe a wad of bills to see to it that his cat is fed. Maybe that’s it. A near comical caricature of machismo and he still retains a little twinkle for his kitty. Unimaginable, perhaps, but we’ll stick to the story.

I’m all for twists and turns and plots brimming with subtext, but when the mood strikes, I can be taken to new heights by the simple and true. No agenda, just the pure, unaffected adrenaline of survival. Not a metaphor for existence, just a man trying to eke out a day so that he may do so again tomorrow. Nothing behind the curtain, as they say. Not even a curtain. Just a series of tough SOB’s, without animosity, beating the living shit out of each other because they’ve run out of options. That’s assuming, of course, they ever had any to begin with, or would, once the fog lifts. If I’m short on detail and lean on exposition, making this less a review and more my usual nonsense in search of an idea, just remember that it’s all per the direction of Chaney himself. Shirtless, because an article of clothing invites an observation. And an observation leads to a conversation. And no, he’d rather not. Neither would I.

Leave a Reply