“Technology advances, but humans don’t. We’re smart monkeys, and what we want is always the same. Food, shelter, sex, and in all of its forms, escape.” Takeshi Kovacs, Altered Carbon

All drugs, be they of the pharmaceutical, legal, or illicit variety, have, as far as I’m concerned, just ONE simple function: to make you feel better. That’s it. If you’re lucky, you might also expand your mind a little, but for the most part, drugs make you happy. There’s nothing more to it than that. And that’s fine. Humans have been using mind-altering drugs from the very beginning, and I can’t blame them. If I were a caveman who just realized he does NOT have eternal life and instead will die, with absolute, horrifying certainty, then yeah, I’d probably want some measure of escape, too. Any will do, really. Mushrooms. Cacti. Jimsonweed. Anything that makes me forget this horrible cosmic joke. You may also, inadvertently, become an enlightened being, for whatever that means.

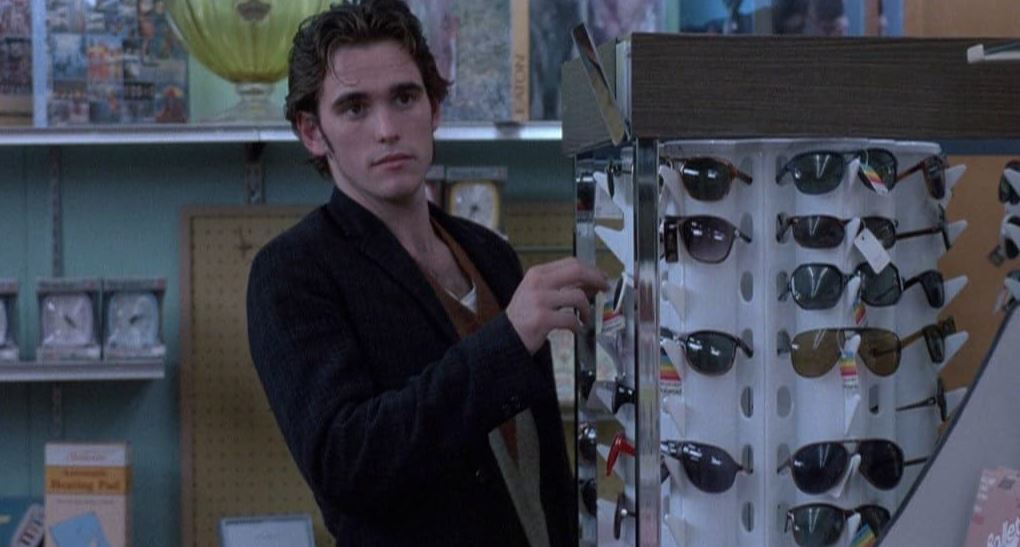

Bob (Matt Dillon), however, is not. Not yet, anyway. Bob is 26 years old, and he and his crew of misfits live in 1971 Portland, Oregon, where they rob pharmacies to pursue their own form of escape. Aside from Bob, his little gang consists of his wife Dianne (Kelly Lynch), his best friend Rick (James LeGros), and Rick’s girlfriend Nadine (Heather Graham). They drift from apartment to apartment, motel to motel, always moving, always chasing the next high, the next score, the next stretch of time where things don’t hurt quite as much.

And since Bob is a smart monkey too, he is acutely aware of the difference between larceny and armed robbery. So they never use guns. No threats. No violence. Their method is: create a distraction out front, wait for the pharmacist to come running, then Bob slips over the counter and empties the drawers. Easy.

Bob also believes strongly in signs, in omens, in what he calls “the code.” The most important one? No hats on the bed. To him, it’s not superstition—it is law. A hat on a bed is a hex, and a hex means bad luck, and bad luck means prison or death. He treats this system with the seriousness of religion. And everyone around him learns to live inside it, because when you’re strung out, a rule—any rule—is a kind of anchor, something that keeps you from losing what’s left of your mind altogether.

Then Nadine dies. Overdose. And the hat is on the bed.

Bob’s world cracks. The superstition becomes real, because grief demands form, and the only form he has is the code. So he does something he has never done before: he leaves. He gets clean. Methadone, factory job, small motel room. A quieter life, if not a happier one.

But escape is escape, in all of its forms. And Bob has never truly stopped believing in the cosmic joke. So when gunshots come, and blood, and sirens, and the ambulance doors close, he decides the debt is paid. The universe has balanced. The hat is satisfied.

And the hospital he is being taken to?

Well…

It’s the fattest pharmacy in town.

Widely considered Matt Dillon’s best work and directed by Gus Van Sant, Drugstore Cowboy tells its story the way it is filmed: in stark daylight. Ultimate lesson learned: none. There is no escape. The joke continues. Forever.

Leave a Reply