If you’ve watched a recent basketball movie, you’ve probably felt that dull letdown when everything looks too polished and never captures the raw edge of a real pickup game. The courts are spotless, the jokes are safe, and the stakes feel like they came from a marketing brief, not lived experience.

That’s why going back to White Men Can’t Jump hits so differently. It carries the noise, tension, and quick jabs that make streetball feel alive. It treats the game as a grind instead of a showroom.

If you’ve wondered why newer hoops films fall flat while a 1992 classic still feels sharper than anything released since, here’s the answer.

The honest friction of the original

What separates the 1992 original from its successors is tonal honesty. The story follows Billy Hoyle, the guy everyone misjudges at first glance, and Sidney Deane, the slick talker who knows every angle on the court. They team up for quick payouts, drift apart when pride gets in the way, and circle back because neither one can outrun the pressure waiting at home. The plot looks like a simple hustle, but it carries enough tension with money, loyalty, and ego to make every game feel like a turning point.

What that story really shows is how people build identity under stress. Billy uses the fact that players underestimate him, and Sidney uses charm to stay one step ahead of a world that’s never been especially kind to him. The movie treats all that as normal terrain, not a setup for a tidy conclusion. The grind feels real: bills don’t wait, relationships bruise easily, and one bad shot can throw everything out of balance. That honesty gives the film a pulse that newer entries never manage to match.

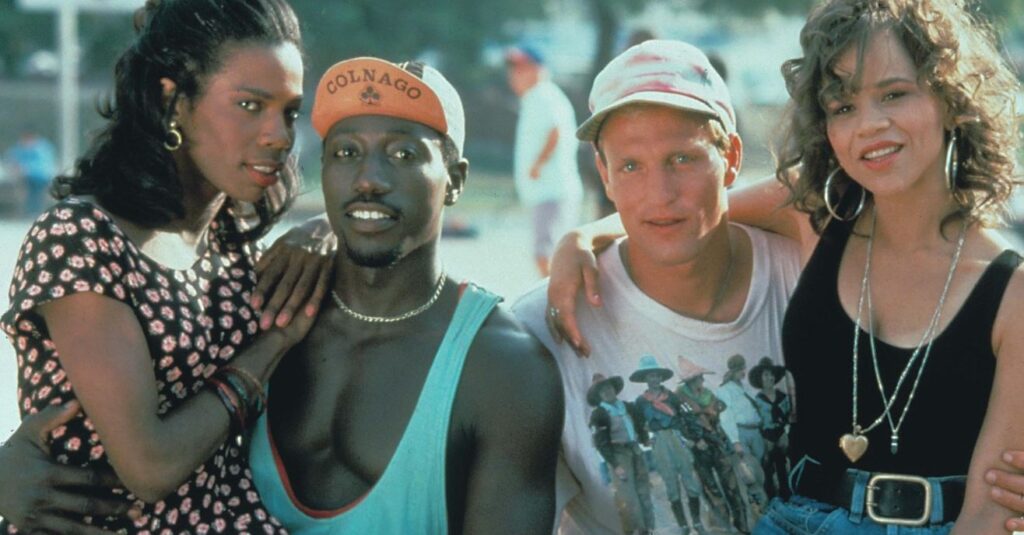

The part that keeps us coming back is the energy around the edges — the trash talk, the steady rhythm of the games, and the chemistry between Harrelson and Snipes. Nothing feels inflated. The basketball looks like actual pickup play, not a highlight reel. The jokes land because they come from pride and pressure, not from writers aiming for easy laughs. It’s the rare sports film that understands the court as a place where people reveal themselves, and it keeps that spirit alive from the first scene to the last.

The post-’90s slide into safe nostalgia

Since the ’90s, many basketball movies have pivoted away from street-level stakes toward feel-good family tales, brand-driven nostalgia, or marketing exercises. Uncle Drew (2018) — built from a Pepsi ad campaign — plays like a friendly promotional sketch inflated to feature length, and reviewers noted a reliance on formula and product placement over real heat.

Remakes and reboots tried to bottle the original’s flavor and failed. The 2023 White Men Can’t Jump remake drew sharp commentary for replacing texture with polish, for using editing and stunt doubles where the original used real court chemistry. The new film lacked the friction that made Shelton’s picture feel lived-in.

Why modern filmmakers lost the nerve

Modern basketball movies struggle due to several reasons, and a sharp turn of the sport’s culture after the ’90s is one of them.

The game shifted from street-level improvisation to a polished entertainment product driven by superstar narratives, sponsorships, and global branding. LeBron James sits at the center of that shift as a media force who shapes how stories around the game are presented. This change built a nostalgia for the rougher edges of the past, when pickup hoops felt unpredictable and personal. That nostalgia rises every time a new, glossy basketball film tries to sell swagger without the chaos that gives it meaning.

That loss of unpredictability also explains a lot. Streetball thrives on mismatches, ego clashes, and a willingness to get embarrassed or do the embarrassing. Modern basketball entertainment sells perfection and celebrity instead.

You can even see the shift in how people place their wagers. What used to be a few bills tossed on a backyard grudge now lives inside polished digital systems, where basketball betting with Bitcoin feels as normal as checking a box score. Crypto platforms and major sportsbooks turned wagering into another branded feature, distancing it from the messy, personal stakes that shaped the old-school court culture.

Filmmakers follow that same pattern. Studios stick to safe stories with familiar cameos, nostalgia callbacks, and tidy emotional arcs. They avoid the kind of trouble that gave White Men Can’t Jump its bite — the risk of losing money, dignity, or trust right there on the asphalt. Without those stakes, the movies feel weightless.

Instead of characters who make questionable choices under pressure, you get soft conflicts wrapped in product placement. That’s why newer basketball films slide off the screen so easily: the nerve, the grit, and the willingness to let a character look foolish for the sake of the story all disappeared when the sport became too smooth to touch.

A last, simple plea: make the gritty reboot

The audience for a truthful basketball film still exists. A clear path to better movies exists, too: cast actors who can actually play or cast real streetballers and shoot like the camera knows a pickup court. Keep the dialogue sharp. Keep the losses meaningful. Make the stakes small and human, not product placement and nostalgia beats.

Call the studios out: stop packaging basketball as a safe spectacle when the toughest, truest stories live in the margins. Give a director the budget to chase the ugly plays, not the pretty ones. The only satisfying reboot will feel like a loss the first time, and a lesson the next. The rest can keep their halftime dances.

Leave a Reply